Below is a short introduction to a portion of a panel discussion by the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism (IISHJ). The title of the panel was Arguing Jewishly. I chose to talk briefly about the Jewish tradition of civil discourse and a way of having discussions based on Street Epistemology. I cannot think of a better time for us to dive into learning to have civil discussions.

Hello, welcome. Since our topic is about creating a civil way to have discussions based upon our Jewish tradition, let’s start with an uncivil discussion – one we are likely familiar with if we spend any time on social media.

Jess: You can’t live a moral life without God

Allie: That’s ridiculous. There are plenty of atheists who are morally responsible!

Jess: Nope – scratch the surface and you’ll see that they were raised by God fearers.

Allie: that’s not true – we are third generation socialists!

Jess: Ahhh, so you’re not really moral at all. You think capitalists are scum. You believe in revolution. You have no moral compass.

Allie: That’s absurd. We care more than you do!

Jess: You’re ridiculous – look at history – Stalin!

Allie: Stalin wasn’t a socialist!

Jess: oh, yeah!

Allie: Yeah! Look at the crimes committed by God infused true believers – the Twin Towers!

Jess: That’s not what I’m talking about.

Allie: God is God – you don’t know what you’re talking about. What idiocy!

and so on and so on….

So might go a modern uncivil argument. Before my 8 minutes are over, we’ll look at an alternative form of this argument.

We already have a model for civil discourse in the Jewish tradition.

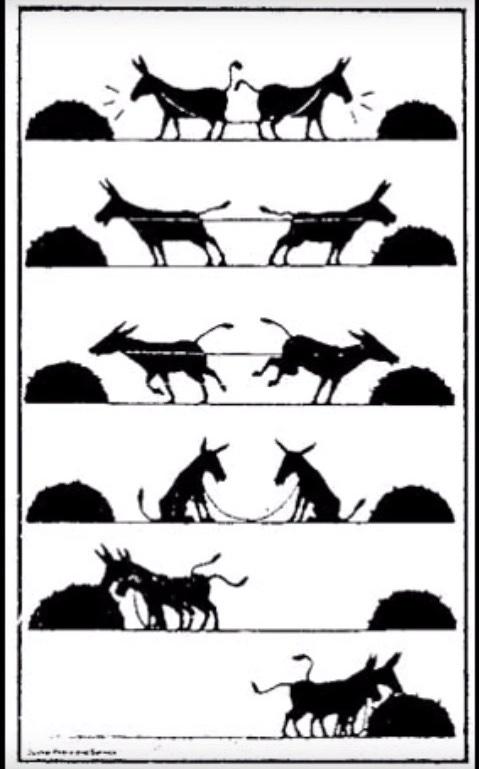

The Sages; that is, the voices heard in Mishna and Talmud, our post-biblical, rabbinic literature, made a distinction between arguing for the sake of heaven. [Makhlokhet L’Shem Shemayim] or arguing like Korach. For the sake of heaven – read as for the benefit of all or for the greater good. Korach, they argue, who rebelled against Moses and was swallowed up for his rebellion, argued for the sake of his own ego.

The sages weren’t always civil. Their civility evolved from the violent expression of disagreements between the house of Shammai and the house of Hillel. There is a story in which the students of Hillel are slaughtered by the House of Shammai, but the latest redactors of the Talmud, made sure to edit and add to stories to require respect of all parties in an argument.

I read a page of Talmud a day and recently came upon a passage where one Sage called another a fool and I could feel the difference from all other passages I had been reading over the course of the past few years. Then – boom – a line later the beam of the study house falls over and the walls start to come down – all due to the lack of respect between these two scholars.

You can find clear messages in Talmud regarding how to treat each other during arguments. Here are a couple examples.

Anyone who humiliates another in public, it is as though he were spilling blood.

Bava Metzia 58b

It is more comfortable for a person to cast himself into a fiery furnace, than to humiliate another in public

Bava Metzia 59a

So what do arguments have in common in the rabbinic tradition; what is argument for the sake of heaven – read – for the benefit of all – for the greater good?:

1. Debate the issues without attacking people and harming relationships.

2. Check your motivation: are you trying to win an argument or solve a problem?

3. Listen to the other side and be open to admitting that you might be wrong.

4. Consider that you both may be right, despite holding opposite positions.

What rules did our friends Jess and Allie break.

1. they attacked each other

2. they just want to win their argument

3. they were not listening to each other and neither want to admit they may be wrong

4. are they both right – maybe, maybe not – that’s okay

Here is how the conversation might have gone. I’m basing this new conversation on a method called street epistemology. Ask me about that later. Their method fits well with the requirement that we respect each other when we have discussions. They even go a step farther and encourage a person who makes a claim to think through their own process of thought that brought them to make a claim in the first place and even possibly change their own mind.

Jess and Allie – take 2

Jess: You can’t live a moral life without God

Allie: Interesting, you think that a person cannot do the right thing if they don’t believe in God?

Jess: Yes, that’s what I’m saying.

Allie: Interesting. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is your absolute certainty, what number would you rank your claim?

Jess: Hmmm, I’d probably give it an 8.

Allie: An 8, why not a 10?

Jess: Well, I have known some pretty kind and righteous people who don’t believe in God and I also know some folks who seem to be quite religious, but are selfish and mean-spirited. Hmmm…..

Allie: Any other thoughts that come to mind about that?

Jess: I’ll think about this. Thank you.

What is the change in orientation shown by this second way of having this argument? First, it’s not really an argument – it’s a mutual exploration of a claim, with two people who show respect to each other and who are looking for the truth – as unreachable as it may be. It’s a start.

To have this sort of discussion requires what I’m terming the three c’s.

Composure – Compassion – Curiosity

Composure – not being reactive

Compassion – caring about the person you are talking with.

and Curiosity – genuine curiosity – if you respect someone, be curious about what process led them to their claim.

Yehuda Amichai intuitively favored this approach in his poem,

The Place Where We Are Right. I’d like to end with this powerful poem.

by Yehuda Amichai

From the place where we are right

Flowers will never grow

In the spring.

The place where we are right

Is hard and trampled

Like a yard.

But doubts and loves

Dig up the world

Like a mole, a plow.

And a whisper will be heard in the place

Where the ruined

House once stood.

Thank you.

Postscript: This talk was given at the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism. https://iishj.org

The broad movement that this institute serves is The Society for Humanistic Judaism. https://shj.org

Street Epistemology is taught online and you can find many YouTube examples. If you would like free training in street epistemology go to: https://streetepistemology.com

A group of members of The Middle Way Society, including myself, are studying and practicing street epistemology. Check us out. https://www.middlewaysociety.org

I have been religiously listening to

I have been religiously listening to