As an adult I’ve spent the last 56 years or so being quite ambivalent about the state of Israel, though I know in my gut why people thought that they could solve the problem of Jewish survival by creating this state.

A little personal history: My grandfather came to Palestine from Poland with his family in 1903. They settled in Petah Tikvah. My grandmother left Poland and arrived there around 1906. They met and married in 1911. My grandfather, Sol, wanted to move to America, but my grandmother refused. “I will not change one gentile nation for another gentile nation,” she was quoted as saying. My grandfather had a different opinion. I may have invented a reason that he wanted to leave Palestine, but the narrative I imagine is that he, fluent in Arabic, was happy with the coexistence of those early days of Petah Tikvah. The Labor Zionists who were becoming more active, wanted to only hire Jewish labor. Whether this was the reason or not, he chose to move to America and tricked my grandmother into leaving. She thought the trip to Chicago was to visit relatives, but Sol had no intention of returning to live in Palestine. Sol and Minnie lived in Chicago and had six children. One year after Sol’s death, in 1969 Minnie, age 77, moved back to Petah Tikvah, a place where she wanted to live the rest of her life and she succeeded in doing so.

Why do I write the above narrative? Their story shapes my own attitude about Israel. I’m aware that my grandmother’s family, who stayed in Poland, perished. My grandmother lived because she went to Palestine! My, possibly imagined, narrative about my grandfather, his ability to coexist with Arab neighbors and the later undermining of that coexistence fuels my identification with the perspective that the exclusionary path was a dead end. It surely seems to have resulted in war after war.

What happens in Israel affects Jews everywhere, and, of course, affects Palestinians, too! Ever since October 7th, 2023, when Hamas brutally murdered and kidnapped Israelis and this vicious war began, I’ve been forced to face my attitude about Israel. I’ve been appalled by the black and white divisions among people I know – totally backing Palestine – totally backing Israel. Early on, there were demonstrations that included Israelis, Palestinians, and local Jews who were demanding a cease fire and return of the hostages. My husband and I went to these demonstrations but there were very few people there. People want to side with one side or the other.

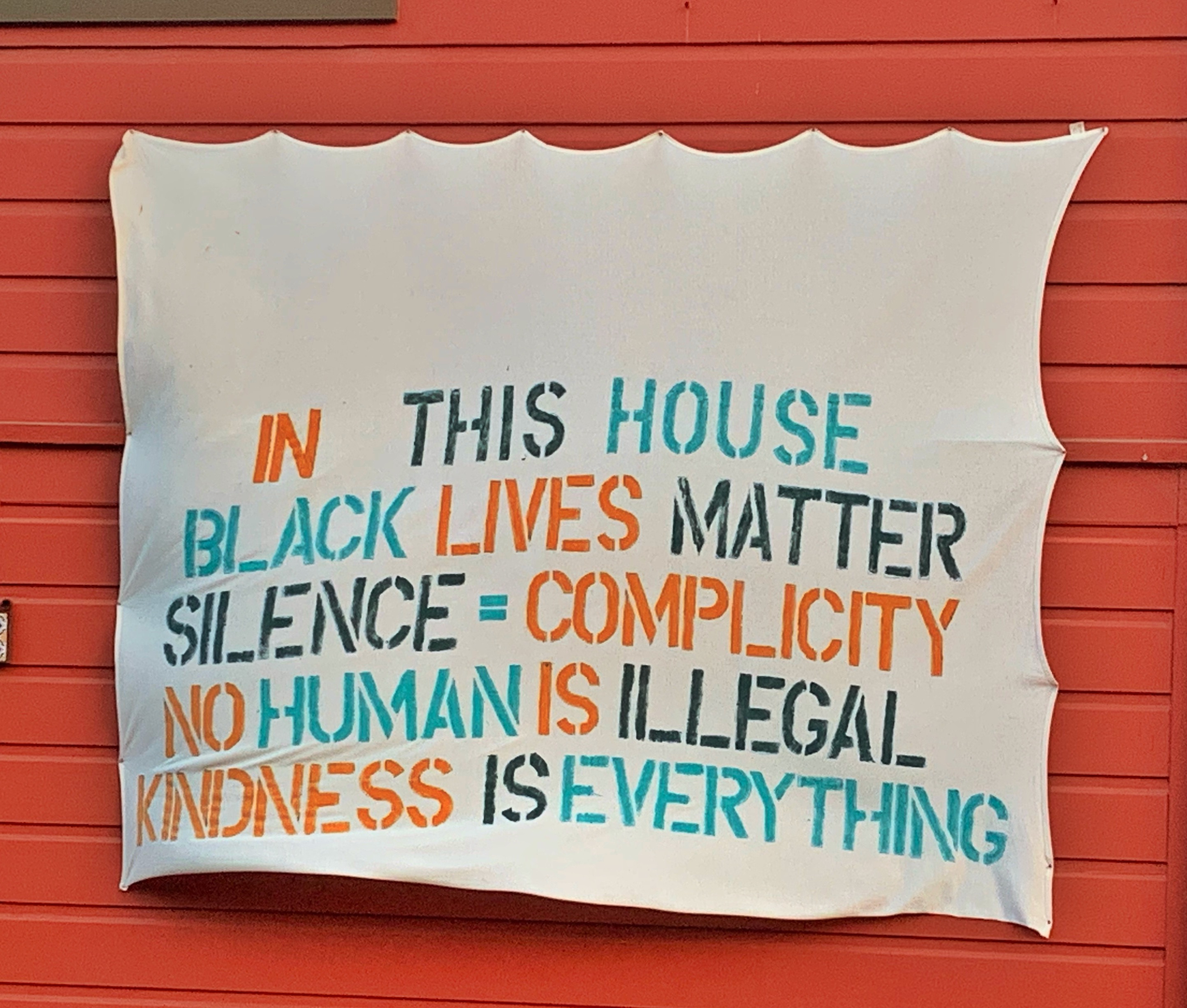

Now is the time for more nuance. After demonstrating last Monday with about 30 rabbis with various attitudes toward Israel, blocking traffic in front of the Israeli Embassy, demanding an end to the war and humane treatment of Gazans and Palestinians in the West Bank, I had to ponder whether or not I would join the Israeli ex-pats and other local Jews at a demonstration in solidarity with Israelis in Israel and across the United States demanding an end to the war, surge of food for Gazans, and return of the remaining hostages. I knew there would be Israeli flags everywhere at this demonstration. I decided that if I were to go to this demonstration I’d have to design and display my own flag. Decide for yourself what this flag means – there can be multiple meanings. Let’s ponder a way forward and listen to Yehuda Bauer’s words:

“Thou shalt not be a victim, thou shalt not be a perpetrator, but, above all, thou shalt not be a bystander.”

I belong to an

I belong to an  Yes, I am baking sourdough country loaves and English Muffins and challah. I don’t think it’s an accident that so many of us are baking bread right now. Whether your yeast is store-bought or created, yeast grows – it’s alive, it’s kneaded and needed, and it helps to create a beautiful, delicious food that feeds the body and the soul.

Yes, I am baking sourdough country loaves and English Muffins and challah. I don’t think it’s an accident that so many of us are baking bread right now. Whether your yeast is store-bought or created, yeast grows – it’s alive, it’s kneaded and needed, and it helps to create a beautiful, delicious food that feeds the body and the soul.